The Pioneers

Charles Mochet

Prior to the First World War, Msr. Charles Mochet built small, very light cars in France. His wife feared the common bicycle was far too dangerous for their son George, so Mochet built him a four-wheeled pedal car. The pedal car reduced the danger of falling over as expected, but more importantly, it proved to be incredibly fast. The boy was delighted when he easily outpaced his friends, who were still on standard bicycles. This drew attention, and soon many of those children wanted pedal cars of their own.

Mochet ultimately decided to set cars aside in favor of building human-powered vehicles. He built a pedal car for adults that he called “Velocar“. It had the comfortable seating position and the trunk of a car, with the pedal propulsion of a bicycle. By the end of World War I, France’s struggling economy meant buying a “real” car was impossible for most people, but Mochet’s Velocar was affordable. Sales increased steadily for the next two decades. Mochet Velocars were practical and surprisingly fast, sometimes being used as pace vehicles in bicycle races. But at higher speeds,

The First Recumbent Bike

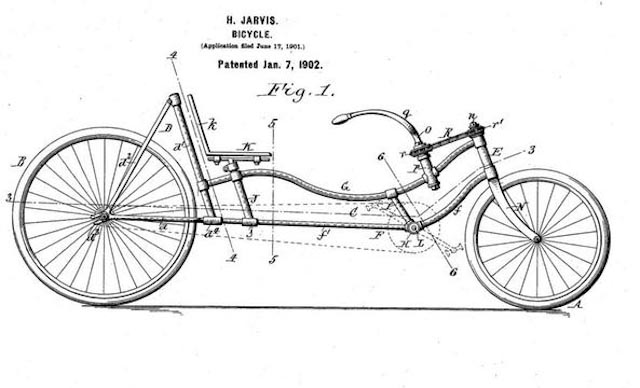

This gave Mochet an idea: Divide a Velocar in half and remove the fairing to create a recumbent bicycle. This included a bottom bracket or “boom” that was adjustable to the driver’s height. The height of the seat was also adjustable. An intermediate drive provided gearing. Mochet not only wanted to show that the unfaired recumbent bike was faster than the common bike, but that it was also highly suitable for touring and every-day use.

Mochet was now on the lookout for a good rider to compete in cycling events with his new recumbent. At first Mochet had a professional cyclist named Henri Lemoine, ride the recumbent tricycle. Henri was astonished at the tricycle’s comfort, speed, and how easy it was to steer. Even so, he couldn’t be convinced to ride the Velocar in contests.

Francis Faure

Mochet then acquired the services of Francis Faure, brother of the famous cyclist Benoit Faure. Francis was a decidedly lesser rider than either Lemoine or his brother Benoit, but he was the first serious cyclist who really took an interest in Mochet’s recumbent bike. After a few test rides he decided to enter a race riding it. The other riders laughed at him.

“Faure, you must be tired and want to go to take a nap on that thing. Why don’t you sit up upright and pedal like a man?”

They quit laughing when Faure left them all behind. It wasn’t even close!

One after the other, Francis Faure defeated every first-class track cyclist in Europe, taking advantage of Machon’s recumbent’s clear aerodynamic superiority. Frustrated riders couldn’t even draft his funny bike. Faure was practically unbeatable in 5000 meter distance events. Early recumbent cyclists had handily beaten their competitors at road races.

The Ultimate Cycling Record

Charles Mochet, his son George, and Faure decided to attack the hour world record, which had been hotly contested for approximately 30 years. However, they anticipated a problem with the recumbent’s natural aerodynamic advantage.

Various bicycle designers had always experimented with fairings and nosecones to improve aerodynamics. At a 1914 race of these streamlined bicycles, world champion Piet Dickentman and European champion Arthur Stellbrink raced each other. Dickentman crashed his bike, resulting in his death. With the loss of the sport’s world champion, the UCI specifically prohibited add-on aerodynamic fairings or nosecones. The faired racing events soon fell into obscurity.

So, in October of 1932, Mochet wrote the UCI (Union Cycliste International) to be certain that a recumbent cyclist’s achievement would be acknowledged. The reply was promising. “It has no add-on aerodynamic components attached so there is no reason to forbid it.”

The existing record had been set by Swiss cycling idol Oscar Egg, who covered 27.4 miles (44.247 km) in 60 minutes in 1913.

On July 7th 1933, Francis Faure rode a recumbent 27.9 miles (45.055 km) in one hour, smashing the previous record and grabbing the media’s attention.

The Recumbent Ban

As more pictures were published, more questions were asked.

Is this actually a bike? Will the Faure record be acknowledged? Is the common upright bike obsolete?

When the 1913 record was also surpassed by an upright later in 1933, a decision became absolutely necessary. The newfangled recumbent was hotly debated at the 58th Congress of the UCI in 1934. Some were impressed that the recumbent was so fast and safe to ride, saying that it could be the bicycle of the future. Others felt it was not a bicycle at all.

Many felt that bicycle competition should be between cyclists, not bicycle designs. Faure was still considered one of the lesser riders, and it did not make sense that he should set the most important record in cycling.

The UCI re-defined exactly what was or was not a bicycle. Recumbents were banned and the upright record was made official by a 58-to-46 vote. Had the UCI had decided otherwise, a lot more riders might be riding recumbents, while upright bikes would seem as quaint as penny farthings.